Unabated mobilization in Kashmir’s women campuses might have been tagged as the ‘defined moment’, but with Kashmiri women always being at the vanguard of the valley’s wrath, the phenomenon appears nothing new.

A year before the Pakistani Gibraltar army in the garb of Mujahideen came as far as Batamaloo, Kashmiri girl students had rocked Lal Chowk with Ae Mard e Mujahid Jaag Zara slogans. Assembled in Srinagar’s Pratap Park on July 13, 1964, those school and college girls of many educational campuses sat on the bus rooftops—carrying flowers, flags and banners— and demanded their right to self determination amid the Azaadi chorus.

Some fifty years later, Lal Chowk hosted another gathering, dishing out the same Azaadi tunes. But what was confused as the new, defining moment in Kashmir’s long, drawn struggle for the right to self determination was only the continuation of the pathway probably treaded by the mothers, the grandmothers and the great-grandmothers of those school and college girls, who sang songs of liberation, “Aye Maula De’dey…”

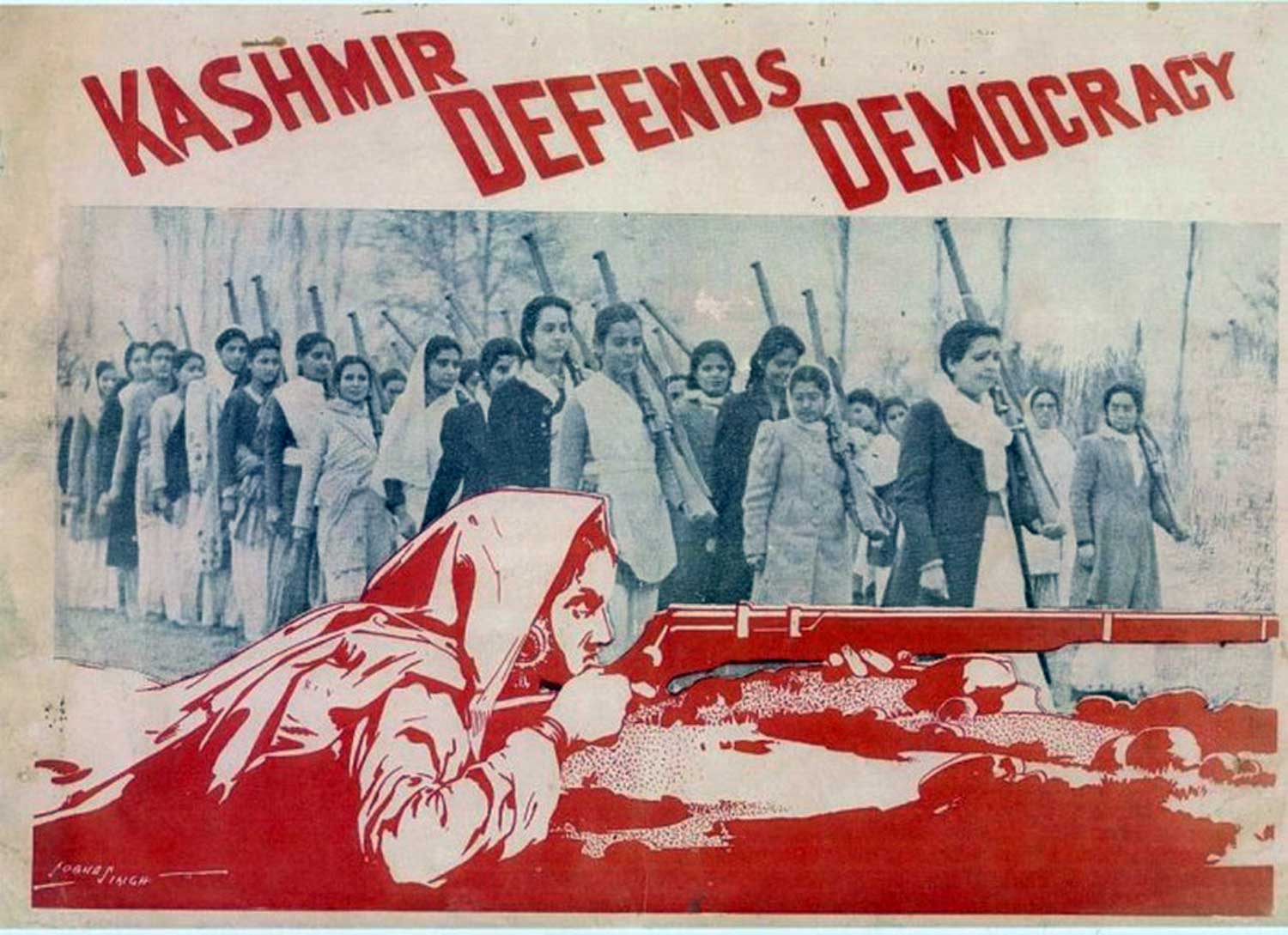

A 1948 pamphlet showing members of the WSDC – the woman shown aiming her rifle is a likeness of Zoon Gujjari. (Source: andrewwhitehead.net)

In fact, right from the day the Mughals occupied Kashmir, says Zareef Ahmad Zareef, a poet-historian, Kashmiri women have been rallying for Azaadi. While men would be tortured, punished, hanged, he says, women would come out protesting against these atrocities.Then came the Afghan period, and the Kashmiri women were targeted, harassed and abducted by the brutal regime, the historian continues. “Women were so much prone to getting abused, that Kashmiris preferred marrying off their daughters during the night time, when Afghan forces would be deep asleep,” he says. “Even then the brides would be abducted by those bestial occupiers.” But despite this brutality, Kashmiri women never stopped resisting, Zareef asserts.

Even the Sikh rule that followed the Afghans was no different, he says. By the time the Dogras ruled Kashmir (1846- 1947), Kashmiri women increasingly rose against the treacherous practice of Begaer—forced labour—the practice that would dispatch Kashmiris (loaded with ration, ammunition, etc) to the China border via Gilgit-Baltistan. Hardly anyone would return alive from those godforsaken lands.

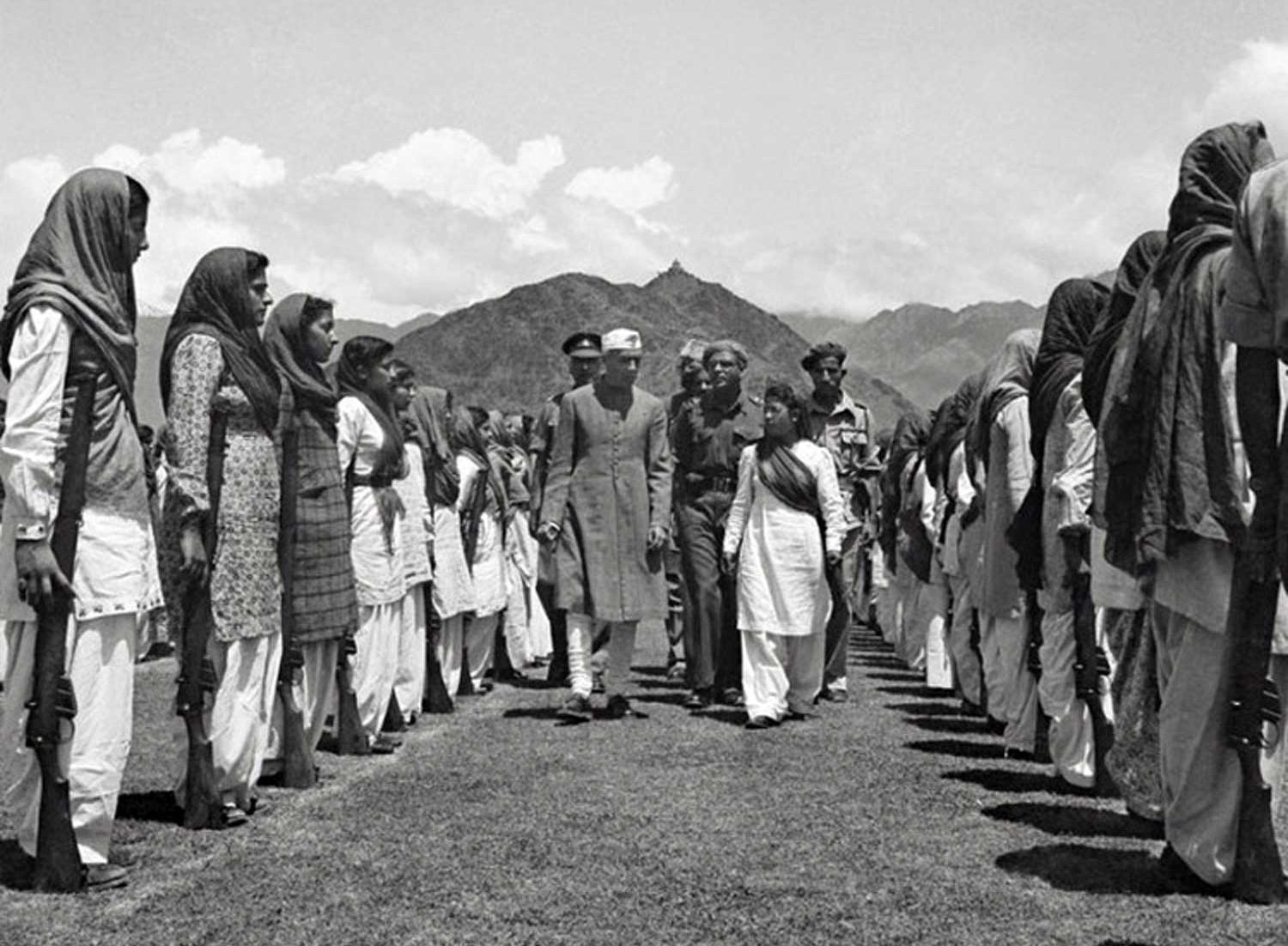

Indian Prime Minister Jawharlal Nehru inspecting the Kashmir women’s militia – the women’s self-defence corps – in Srinagar. (Source: andrewwhitehead.net)

Then, practices like ‘Gow Hathya’ and ban on buying, selling mutton on Tuesdays and Saturdays (and other Hindu holidays) mostly ended up with Muslim men being hung at Zainakote. “Again,” Zareef says, “women would resist against the ruthless rulers on this.” Among those women protesters, the poet says, the female folks of restive Maisuma—known for their hardcore resistance—would take the Dogra soldiers head-on.

“Those women would beat the drums to an extent that horses carrying soldiers would get scared and then would chase them away,” Zareef says. “The same blood is flowing in the veins of these young brave-hearts [girl students] today who are up against the injustices.”

In his book, Srinagar: The City of Resistance and Culture, Kashmir’s well-known commentator Zahid Ghulam Mohammad aka ZGM mentions some intriguing cases where women protesters were killed by the Dogra army for showing their resistance spine. Hailing from every nook and corner of Kashmir, says ZGM, those women made a notable contribution to the movement.

“In 1933, with Kashmir reeling under the Dogra Raj, such enthusiasm was really not expected of these women,” the commentator says. But when Shopian’s Musmat-e Sajia Bano, 25, showed the same spine over the murder of her husband, she was bled to death. “Her killing was perhaps the sign of the coming times,” he says. “She was pregnant and died along with the child on the spot!”

The second woman to be killed that year was Musmaat-e- Jaana Begum, 35, widow of Abel Lone of Khwajapora locality of Nowshera Srinagar. She was killed in the police firing, ZGM says. The third woman martyr was Miss Phretcha, widow of Khawaja Razak Joo Guroo of Mohalla-e- Jalal Sahab, Baramulla. She hurled a Kangri on the face of a police officer in a course of procession of women which disfigured him permanently.

“The Kangri incident tells us that the women were not submissive but combative, not afraid of the forces,” stresses ZGM.

Another woman protester to be killed by the Dogra forces was Musmaat-e Fazi who was the part of a women procession at Maisuma on Sep 24, 1931. “Even when the martyrs were buried in July for the first time,” ZGM says, “women would permanently protest there in Khawaja Bazar where I would live.”

Many of these forgotten women dissenters (including Maisuma’s firebrand Raja Katcher) didn’t care for their lives while resisting the treacherous rule. They were revolutionary volunteers, as ZGM describes them, for the cause, which is continuously engaging Kashmir’s young and restless on the streets and woods.

Later the educated and the elite class of women also joined the female band of fury, ZGM says. Among them were Begum Zaffar Ali, Miss Mahmooda Ali Shah, Sajida Zamir Ahmad, Zainab begum and others, who became political workers in 1946.

Belonging to the progressive school of thinking, many of these elite and educated women resisted Sheikh Abdullah’s decision to go with India. “They never wanted to be with India,” ZGM maintains. “With the result, the two of them faced jail.” One among them was Birjis, wife of the first barrister cum lawmaker, Abdul Gani Rentoo.

A school inspector by profession, Birjis was detained and sent to a Jammu jail. “Some of these women were even exiled and sent across (Pakistan),” ZGM says.

Interestingly, the Women’s College, founded in 1950s, has always remained at the heart of dissent by Kashmir’s women. “I remember the two girl students – Firdous Naqash and Abida Naqash – from the Women’s College singing patriotic song with their melodious voices at the start of the student’s rally,” ZGM says.

Many of these girl students took a rally toward the UN office in Sonwar on March 19, 1964 where the UN Security council was meeting again to discuss Kashmir.

These girl students presented a memorandum to the Lt. General Robert Horald Nimo, the UN chief military observer in Kashmir.

“Such was the level of their political awakening that all the students remembered his name,” ZGM says. “Some girls even made a plea to the Australian General to ensure the delivery of the memorandum in the UN on the same night for broadcasting from BBC.”

Then, ‘Ye Srinagar ki betiyan, Nidar Mujahidun ki betiyan’—Daughters of Srinagar, daughters of brave-fighters—was a song dedicated to daughters of Kashmir, ZGM tells it.

“Some of those daughters I remember are Shareefa Qureshi, Shahi Taja and Shameem Khan. I am sure they might be smiling somewhere by watching the current student uprising. Their legacy lives on.”

There exist countless tales of sacrifice and sufferings by Kashmiri women dissenters while rallying for the Plebiscite Movement. Later as Kashmir passed through political perfidy and subsequent upheaval, the likes of Asiya Andrabi came forth with her Dukhtaran-e-Millat (DeM), a “reformist organization”.

Andrabi who wanted to pursue a bachelors in Biochemistry changed forever after going through a book by Zaynab Al-Ghazali, an Egyptian activist who founded the Muslim Women’s Association. Andrabi’s burka-clad women dissenters group would initially remove the obscene posters of films near the cinemas before taking out anti-India processions in the insurgency hit Kashmir.

That chaotic period flipped many lives including that of a newly-wed bride of Batamaloo, who made ‘Go India, Go Back’ resolve her new religion.

Looking out of a windowpane “shattered” by CRPF men two months back, Munawar Sultana says, she broke another windowpane of her home to deliver a loud and clear message to the armed forces: “I am not scared of you! I will keep on fighting! I am unstoppable!”

At 46, Sultana carries stamina of a teen protester. She considers her high-pitched voice as God’s gift—for it helps her during the protests to raise the slogans of Azaadi. Unlike her neighbours, Sultana comes out fearlessly to protest without covering her face, for she believes, she is fighting for the right thing.

The widow had been participating in anti-India protests before 90s too — but after April 8, 1993, she made sure she did that religiously.

Sultana had passed her matriculation exams, and after turning 22, she got married to Gowher Amin Bahadur of Batamaloo’s Danderkhah area. Bahadur—a handsome man with a chiseled face and gifted with rebel courage— was one year younger than Sultana, she asserts.

The couple lived happily for 4 months, 7 days—before one Eid at her maternal house at Batamaloo, doomed Sultana’s dreamy world.

On the fateful day, Bahadur was invited by Sultana’s parents as per the Kashmiri tradition to have a feast on their first Eid together. But even before tasting the food, Batamaloo was cordoned off by soldiers and a crackdown was announced. Women stayed at home and the men were taken to Batamaloo bus-stand. Sultana says, Bahadur had tried to provide water to the thirsty old men and children who were present in the parade. But her beau’s Samaritan nature annoyed the commanding officer, JS Shekhawat.

“He briskly rounded up three men,” Sultana says, “including my husband. They were taken to a nearby cowshed where the two of them were killed.” Among the slain duo was Sultana’s world — her Bahadur. Only one man was released to recount the horror and apparently to reinforce the regime of fear.

“Shekhawat had told him, Woh jo tumhara baap ban raha tha, usko hum ne maar diya [The one who was trying to be your father, we have killed him]. For what? For what, I ask? For providing water to the thirsty?” asks Sultana, in a choked voice.

It was a cold blooded murder. He was fired on the back of his head and chest. In his passage, the fear of the worst was gone from Sultana’s life. Months later, she gave birth to a child who never saw his father. Shortly Sultana became the face of women protests in and around Srinagar besides a court regular. She won her case registered in Lower and High Courts. At present, she is fighting against the BSF and is hopeful that justice will be served to her.

She has one ideology now: No one should suffer like she did. For this, she says, she is ready to die, or sacrifice even her son’s life, if that would ensure that the coming generations of Kashmir would be free. “I say, kill lakhs of people here. Kill me as well. At least, the one or two who will survive will live freely. At least, they will have their right,” she says.

Sultana is proud of the girl students who on April 17 came out to protest against the attack on the Pulwama Degree College campus. “With men being tortured and killed, how could women not come out? Why would women seal their lips?” she asks.

“Women have picked up guns, protested peacefully, crossed borders and have always been there, resisting in every possible way. Our freedom is inevitable. We will keep on protesting. Times are changing. This wave is bigger. Even the women under seven veils will come out to protest. You will see,” she says, with her eyes wide open and tears crawling back.

Akin to Sultana, Kashmir houses many such women dissenters. They might be everyday dissenting, but not all of them stand documented.

“We don’t have any data regarding the women who came out to protest during the early history,” says Khurram Parvez, a rights defender. “But it is all alive in the public memory. The issue is that we are asked to provide evidence even about things that we have witnessed with our eyes.”

Government Women’s College, M A Road Srinagar students along with injured colleague during a protest against the authorities. (Photo Courtesy: Excelsior)

Women massively protested in 2008, 2010, he says. “Now the difference is that the girl had a basketball in her one hand and a stone in the other. This was something new that the media harped on. Otherwise, it’s not new. In 1950s, ’60s, women would come out with sticks. The only difference remains, it is being documented now.”

But despite lack of images and videos, a stark semblance between Now and Then is quite obvious. ZGM still remembers one fiery lady from downtown who would lead the protests. “The image of Saaja of Khanyar, a devotee of Mirwaiz Yousuf Shah, with black burqa flying in air like superwoman’s cape, raising full throat slogans, still lives in my memory as an embodiment of angst and resistance.” That was the image of 1965.

Some 52 years later, in 2017, Kashmir literally witnessed the resurgence of Saaja when an image of a girl protester whose black burqa flying in air like superwoman’s cape was clicked somewhere in the simmering streets of Srinagar. For ZGM, it was coming of the (new) age in Kashmir’s vintage women rage.