As the world celebrates September 15 as International day of Democracy, calling for effective and inclusive democratic governance with respect for human rights and the rule of law, Gurez—a ‘godforsaken land’ situated at a distance of 120km from Srinagar—is grappling with armed forces concentration, basic amenities and frequent frontier fireworks.

Dawar (Gurez): As the main town was in full bloom, with locals overjoyed to be a part of the annual tourism festival, the military routine seemed natural. Three days later, as the festival concluded and the Habba Khatoon peak dipped in moonlight, the locals sat on pavements, apparently, to mull over the military routine that they have to restart and relive the next dawn.

The festival that saw who’s who in State making their presence felt in Gurez was the new ‘hope’ for the locals—a clear departure to their militarized lives. But the moment they embrace the perpetual uneasy calm in their backyard all over again, their jittery lives surface at once.

Perhaps dwelling at the Line of Control (LoC) in the times of peaked Indo-Pak hostilities has its own perils, making Gurezis suffer in silence.

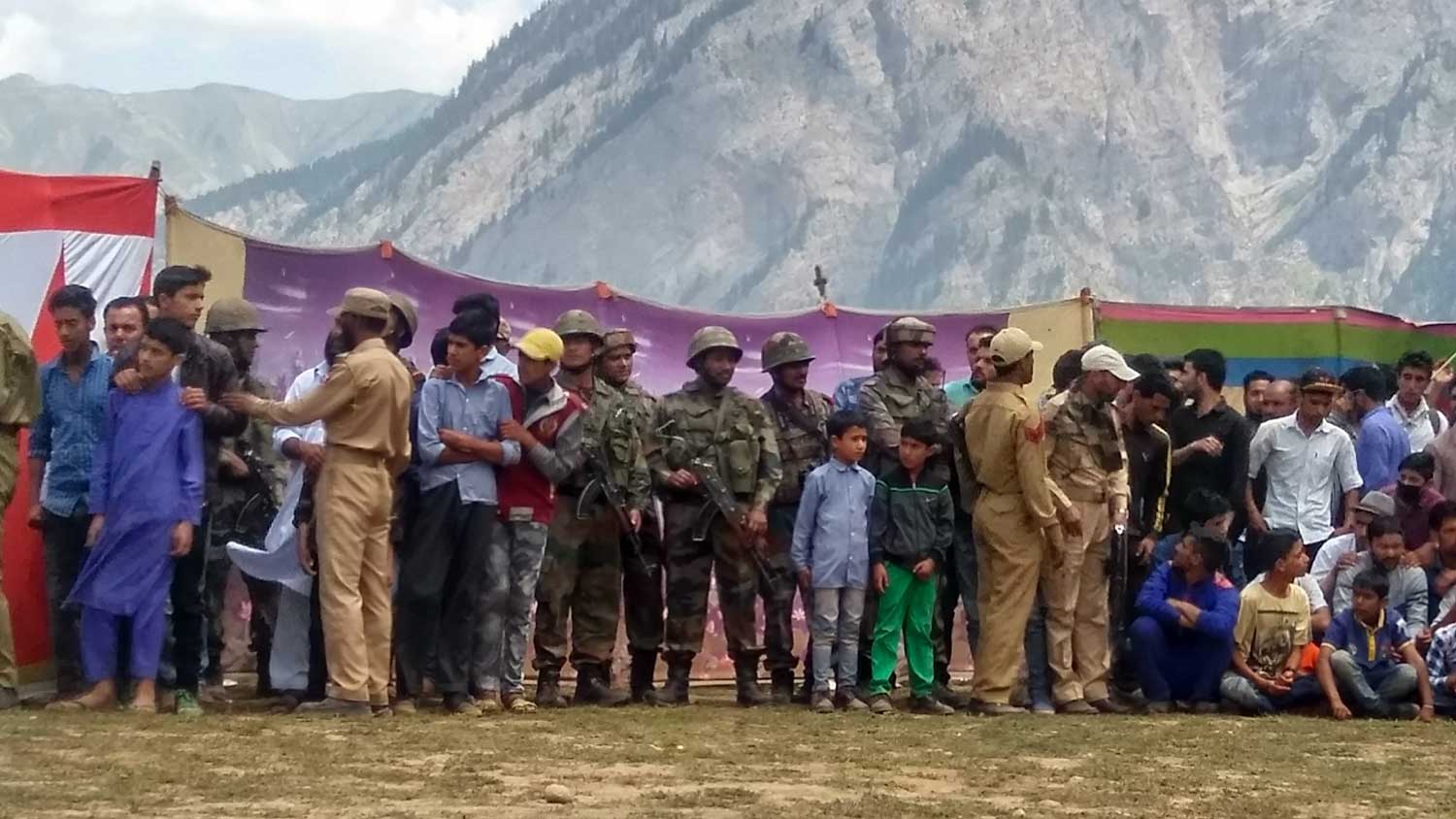

Recently when the locals went to ‘celebrate’ the August 15 as India’s Independence Day inside a local garrison stretched over agrarian and orchard lands, Dawar and other areas had a day off. The army band that sang patriotic song—Dil diya hai, jaan bhi dienge… Aye watan tere liye—made cheerleaders out of blank-faced locals amidst alerted troopers, pot-bellied cops and some local boys in Territorial Army uniforms.

Being a mini-model of the most complex frontier systems of the world, Gurez with its frontier populace remains the worst victims of oppression. They have diminutive control over their environment, actions, choice of living and livelihood.

“Do we even have a choice to say ‘No’?” says Mushtaq, a college goer, who keeps shuffling between Srinagar and Gurez for studies. “We live in a garrison, where our actions and choices are being dictated upon.”

Such military directives and dictations make them extremely vulnerable to physical and psychological damage as they lose control over their own self. Under such situation, how people sustain and dream of their future might remain a mystery to the outer world—and perhaps a choicest fodder for gossip and rumour. But for the Gurezis, it’s a daily razor-walk along LoC, barbed from birth to death.

Such is the life beyond the Razdan Pass—the Bandipora-Gurez highway unprotected by guardrails and one of the scariest roads in the world—where Indian army has wrapped life under the rings of concertina wires. The wiring thickens as the slope drops and Bofors and artillery make a common sight.

The upward position of these Bofors covered with olive green net is a topographic indication that the ‘not-so-friendly-enemy’ is at higher position and powerful indeed. Most of the high posts in Gurez are under the control of Pakistan. This makes their strategic position strong.

“One single shot from the other side,” says Aziz, a local, “and an Indian post will be blown to dust.”

The only thing that saves the Indian position in Gurez is the local population living around, Aziz says. The villages in Gurez and many frontier areas are located within the radius of the army posts. Any action from either side means civilian causalities. “Many a times in past,” he says, “the cross-border exchange was stopped only to prevent the collateral damage.”

“Despite an uneasy calm, we are uncertain about our lives,” Aziz says. “You never know when shelling starts suddenly.” And whenever it does, the entire Gurez runs for their lives and take shelter in bunkers. For every 10 households, there exists one bunker in Gurez.

Aziz makes his living from agriculture, but the income is not enough to let him migrate from the place and dream of a better life elsewhere. Otherwise famous for its Zeera, Gurez now strives for its existence because specific areas which produced the finest quality are either under the control of the army or stand in between the barbed wires.

Even the controversial Kishan Ganga Power Project is seen an attempt to assault the natural life-sustenance of the people. Several people have been displaced and the aquatic life existing in the downstream region of the dam now suffers badly.

“There were times when we had to be inside the bunker for 10 consecutive days,” says Mubashir, a resident of Bagtoor. “And we did not know what was happening outside except the loud bangs which gave a clear indication that moving out was unsafe.” Every time they enter the bunker, they remain doubtful of their exit.

“In one shelling, the Pakistani posts stopped firing after a local Masjid caught fire in Bagtor area,” says Mubashir, pointing towards a Pakistani post he was facing.

Amid frequent frontier skirmishes and poverty, many of these people aren’t able to follow their brethren who moved to Bandipora and Srinagar. Many of them are infact oblivious of the changing life trends on the other side of Razdan Pass.

These civilians reside around these army posts from centuries now where they would lead peaceful lives and move across the guarded barriers freely. All that has gone now. There were no barbed wires to guard their movement, then.

But as they continue to stay put, their children have started to become war-weary in a set-up which looks no better than a battlefield despite being an idyllic spot. At times, even their schools become war-zones. Govt School Dagan that faces a Pakistani post in Gurez lately became one such zone.

As guns across LoC traded fire, the students had to run for their lives. Operating from a rented traditional house, the school with three rooms, 28 students and 5 teachers witnessed commotion as students began running and taking refuge in a nearby bunker.

“We have been witnessing this phenomenon since our childhood,” says Yasmeena, a Class 6 student, recalling the day’s horror.

“It feels like a permanent part of our lives now. Although every time such things happen we get terrified and run for our lives.” People have adjusted their lives accordingly now, she says, but the frequent shutdown of school is a matter of concern for her.

The schools are issued advisory by the army to shut till further orders. There were times when schools were shut for months, she says, and now for weeks.

Government school of Dagan which faces a Pakistani post and on the right of the school lies the last Indian post. (FPK Photo/Afshan Rashid)

“Things are very uncertain here,” says Gulzar (name changed), a teacher. “These kids have little exposure to the outer world and prevalent things here are too unpredictable, making these children the victims.” The migration of the educated lot from Gurez is equally contributing to its crisis.

Over the period of time, Gurez has produced some of the known bureaucrats, scientists, engineers and doctors. But these people settle outside and even get their children educated from there.

“Those people don’t realize the social responsibility of changing their other natives,” Gulzar says. “In fact, they use category certificates to reach to positions of power and never return to their land.” Further, as Gurez remains snowbound for most of the year, its educational calendar remains limited.

While the rest of the State has already switched from 3G to 4G networks, these villages are still unaware of the basic telecommunication facilities. Though most of the young generation is equipped with Smartphones, but they have to travel to the heart of the districts to avail network services. For them, Smartphones merely serve as music players and gaming screens.

The road access in Gurez remains to be the domain of defense ministry which extends it to Border Road Organization (BRO) for maintenance. The roads that lead to the last villages—Bagtoor, Silikote, Chandura, Ismarag and Tulail—on LoC are in a mess. Despite the conflict turning 70-year-old, these roads continue to be in such shabby shape.

All these problems alongside crisis in communication, health and electricity have made Gurez a primitive space where locals are struggling for their lives.

Even when the more challenging roads—like the Jammu- Srinagar Highway, the Mughal Road or Simthon Top—have come up, the constant dilapidated condition of roads in Gurez makes it a clear case of strategic decision.

Perhaps in border games, both paths, as well as people, look more of hostages and human shields. Gurez looks no different.