Their Kashmiri roots are either traced as Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s lieutenants or Guru Nanak’s Brahmin converts, but beyond that introduction Kashmiri Sikhs are the vibrant minority who have played their proactive role in Kashmir’s political theatre by always rising above hate and hostility.

Suddenly during Kashmir’s watershed years, one question turned the Sikh minority thoughtful: “Should we migrate from Kashmir?” This query gripped Kashmir’s minority community at the start of militancy in 1989. Then from city and countryside, Kashmiri Pandits in droves were leaving the Valley. Scores of disgruntled KPs blamed the ‘militant agenda of Islamization’ for the migration. But despite the obvious threat perception, Kashmiri Sikhs showed courage and determination and opted to stay put with Kashmiri Muslims.

Behind the camaraderie was the history of the age-old brotherly relationship. Kashmiri Sikhs and Muslims (having no history of communal tensions) only came closer after the former refused to follow the footsteps of KPs.

Being an enterprising community, the Sikhs since then improved in all spheres of life. And today, one could perceive their overall mobility and presence in varied fields of Kashmir’s society. Settled in different parts of Kashmir, they share the common cultural space with the majority community.

The Sikh community in Kashmir defines itself as a distinct ethnic identity with visible distinction on the basis of religion, language and scripture of its own. But there’s no clear narrative of their history in Kashmir. Only varied accounts exist, telling how they established themselves in Kashmir.

Legend has it that Sikhs came into Kashmir as lieutenants of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. But some historical narratives state that Sikhs are local natives. “They were Punjabi Brahmins who were already living here and embraced Sikhism during the visit of Guru Nanak Dev Ji to the Valley,” goes one account.

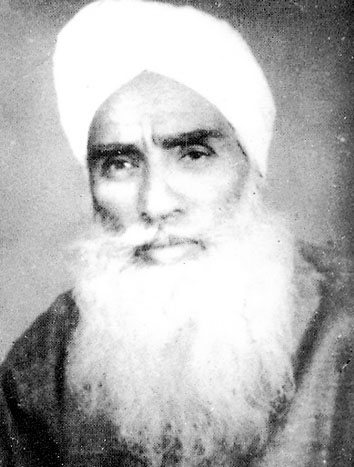

A portrait of Maharaja Ranjit Singh

Michael MacAuliffe aka Max Arthur Macauliffe (Sep 1841 − Mar 1913), a senior Sikh-British administrator, scholar and author who translated Sikh scripture and history into English writes that Guru Nanak made many to embrace Sikhism in Kashmir and thereafter went into the Himalayas.

“The Sikhs came to Kashmir in the service of Raja Sukhjawan, a Hindu who was sent as governor of Kashmir by Timur Shah of Kabul in about A.D 1775,” writes G.T. Viegue who visited Kashmir in 1835.

There’re others who have taken a position that there were Sikhs in Kashmir during the time of Guru Hargobind, the sixth of ten Gurus of the Sikh religion in early 1600s. If true, then it shows that Sikhism existed in Kashmir during the Mughal emperor Jahangir’s time. Some of the old Gurudwaras in the Valley also point to this theory.

The British annexation of Punjab in 1849 eventually resulted in certain reform movements within Sikhism. Most of these reform movements emphasized on the pristine glory of Sikhism and its purification from the slowly creeping corrupt influence of Brahmanical ritualism.

The socio-religious movement in J&K was an offshoot of the socio-religious movement in the un-partitioned Sub-Continent and formed an inseparable part of the same. Then, Kashmiri Sikhs were a small minority and like other communities were equally distressed. They too were denied opportunities of education and employment of the state services. However, they were also affected by the spread of education in the state and changes taking place across Sub Continent in the course of time.

It was in this context that one can see the role of various socio-religious organisations, which helped in crystallization of Sikh identity: Khalsa Dewan, Khalsa Youngman’s Association, Sikh Sahaik Sabha and Gobind Sabhas.

These outfits demanded that Sikhs be given employment according to their rights and claims in all different departments like military, revenue, judicial, medical, police etc. Then, the highest posts the Sikhs occupied were those of few Patwaris or Munshis, showing that the Kashmiri Sikh community was backward in every respect. But this feeble societal positioning didn’t prevent them to form the basis of the struggle for freedom in Dogra-ruled Kashmir.

After 1925, the Sikh outfits jumped into politics and joined the Muslim nationalists, anti-British and anti-Maharaja movements. The Akali Movement had already brought the Sikhs into the vortex of active politics in Kashmir. The episodes of Komagatta Maru, Jallianwala Bagh, Rowlatt Act, Gandhi slogan of Khadi and use of Non-cooperation Movement had brought them much closer to national politics.

Kashmiri Sikhs were also at forefront criticizing the Amritsar Treaty under which the entire human population along with its rivers and mountains were purchased with which Dogras destroyed the Sikh Kingdom of Lahore.

Eons later, in the summer of 1938, they played their role in the changing political atmosphere of Kashmir.

On June 28, 1938, the working committee of the Muslim Conference met at Srinagar and passed a resolution recommending to the general council to allow people to become its members irrespective of their caste, creed or religion. Along with the signatories like Sheikh Abdullah and Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad was the prominent Sikh leader, Sardar Buddh Singh.

Sardar Buddh Singh

In 1939, Muslim Conference was changed to National Conference. When the Quit Kashmir Movement started in 1940s, the Sikhs played their role before the ensued period of turmoil in the run-up to the 1947 events left them strife-stricken.

The partition and the ensued bloodbath distressed the community to an extent that they became a silent minority. By 1957, a big boost came for them when All India Annual Akali Conference was held in Srinagar. Prime Minister Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad assured the Akali leadership that he would help in the upliftment of Sikhs. He fulfilled his promise by providing route permits to many Sikhs for transport business.

Till 1975, the politico-religious Sikh parties kept lobbying for the separate identity of Sikhs. That year, Gurudwara Prabandhak Board Elections were held on party basis between Akali Dal and newly formed Khalsa Panthak Party. The latter won and formed the first Gurudwara Prabandak Committee, which was a watershed moment in the history of Kashmiri Sikhs.

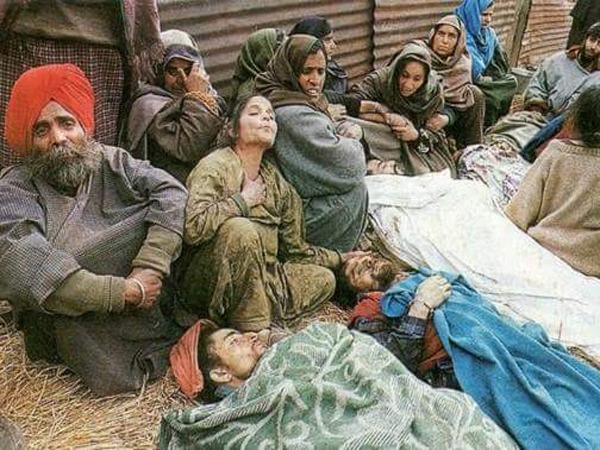

But even after they stayed put in the tumultuous years of militancy, the March Massacre of 2000 at Chattisinghpora in which 35 Sikhs were brutally killed badly rattled the community. The slaughter coming on heels of the visit of US President Bill Clinton to India was the first time when the Sikh minority was targeted. It shocked the entire state.

Again the question, “Should Sikh migrate from Kashmir?”, turned them thoughtful. This had a great impact on Sikhs’ psyche, but they continued to stay put in Kashmir. And from 2000 till date, Sikhs have been vocal of the right of Kashmiri Muslims to have a plebiscite.

The victims of the Chattisinghpora Massacre

Even after the KPs left, it was the Sikhs that provided a source of diversity in Kashmir. They stood grounded despite pulls, pressures and politics. The decision of 75,000 Sikhs to stay back in Kashmir has been appreciated by the majority community including the resistance leadership of Kashmir.

All this makes one believe that it’s not the number, but the Sikh imprints on the history and culture of Kashmir that matters.