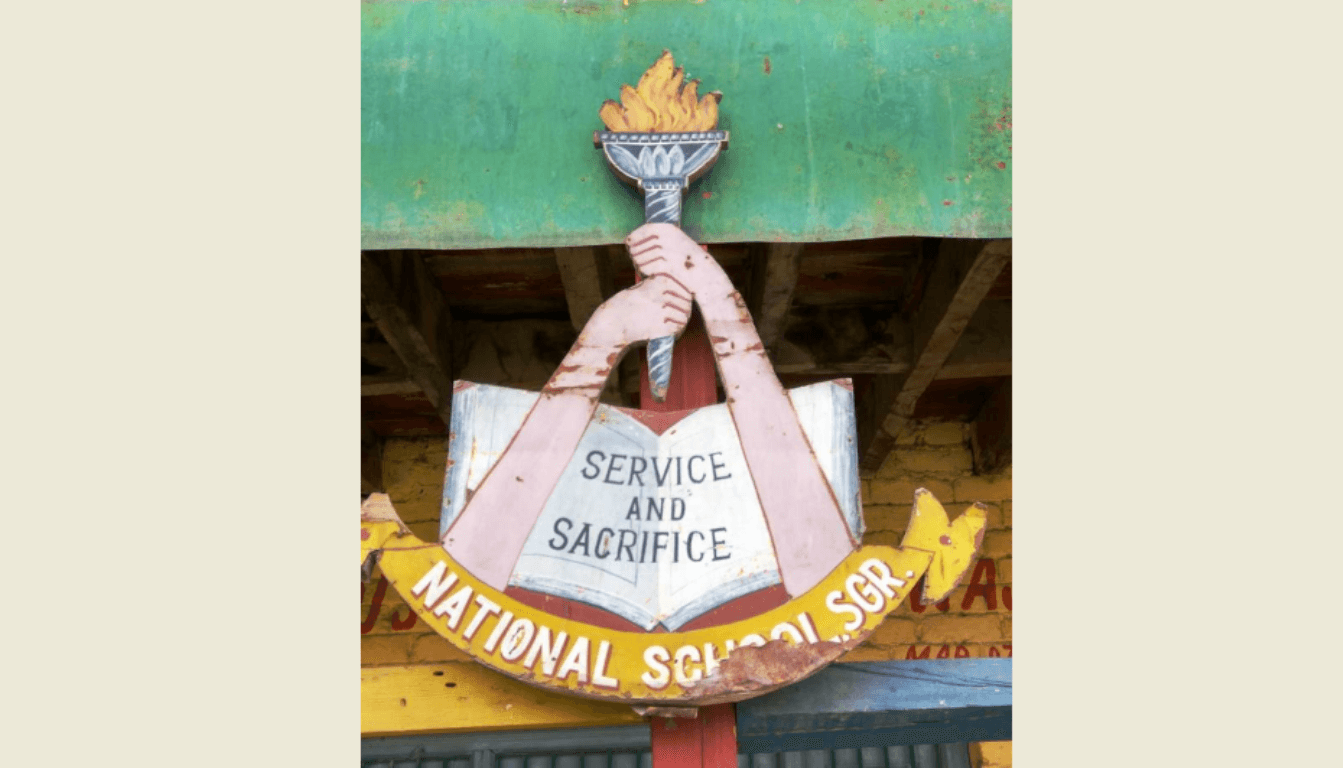

Amid the recurrent assault on the historic city of Srinagar whose heritage sites and buildings are being redone in the name of development and commercialization, National School is facing an existential crisis. Official apathy has reduced the celebrated school of Srinagar to a shabby shelter for four government schools.

Beyond the broken windowpanes and the faded walls, the historic ‘English medium for Boys & Girls’ School is housing scores of students in shabby classrooms. The impact of 2014 devastating flood is still glaring, making the school in the heart of the Srinagar City look like an orphaned structure. On the street outside, the passing alumni—the bankers, the doctors, the traders, the journalists, the pensioners—often steal a glance at their alma mater, National School, to muse and mention: “Kus school ous” (What a school, it was!).

Today, the footfall of National School, Karan Nagar Srinagar, is alarmingly falling, despite the crowded campus façade created by the students of the four Government schools—Middle School Chota Bazar, High School Zandar Muhalla, Middle School Tenki Pora and Govt Middle School Chenkral Muhalla—running from its premises since the 2014 floods.

“The government executives came and requested me to accommodate these four government schools in the building for a few months until some arrangements are made for their rehabilitation,” said Abdul Aziz, Principal-National School. Three years later, the government is yet to make any arrangement for them.

One of the schools running inside the National School premises

After the official deadline was violated by government multiple times, Aziz met the then director education Dr. Shah Faesal in 2015 and sought his help in restoring some lost pride of his school. “But like others,” the peeved principal said, “Shah never moved beyond lip service.” The cold vibes triggered by the official coldness has already dented the once glorious image of National School, whose ground and first floor has been occupied by the ‘guests’.

Before floods, these schools were running in rented buildings. But now, overstay and distant shift have created woes for them. “You can’t run a school from two-rooms,” said Principal Govt. Middle School Chenkral Muhalla. “Most of our students have quit in disgust as washrooms are very dirty here. Scarcity of water further bothers them. Lack of proper cooking room impacts the mid-day meal for children. It’s very risky to cook in an unhygienic place.”

But amid this, National School administration is decrying over the new campus crisis. Free-roaming of the government school students in the school has violated its set standards. “Now, parents of my students question me – is this a government or private school, resulting in 80% downfall in student roll,” said Aziz, downheartedly. The scene, however, wasn’t always gloomy.

As a prestigious school of its time, National School was known for its immense literary contribution to the society. Most of its alumni—both Kashmiri Muslims and Pandits—rose to become the reckoning names and figures. Among them, the honorable mentions included Cabinet Ministers like Ghulam Mohidin Shah and Harbans Singh Azad and Chief secretaries like P.N.Kaul, R.C.Raina and Prof. Nasarullah.

It was in April 1938, when National School was established in Srinagar with D.N. Raina (B.Sc. B.T.) its first head. It was the first ever non-denominational and non-proprietary educational institution to be set-up in Kashmir valley, then having only four schools in Srinagar and one (St. Joseph’s School) at Baramulla. Founded and managed by eminent citizens, the executive powers of the school were given to independent non-teaching members.

The School’s central location helped it to enroll students from all over the city and from all the socio-economic sections. “I remember how the school had an attractive salary structure and provisions for pension in place,” said Parvez Bhat, who had his teaching stint at the School in early eighties. “The school would ensure induction of female teachers, too.”

The available records reveal how the school staff in 1980 was led by one M.A. B.Ed. teacher at the top, followed by 25% trained post graduates, 50% trained graduates and 25% other special line teachers. That year, the data shows, the School’s Class 10th annual exam pass percentage stood at 95.

“Behind those glorious numbers and days were the people like Pandit Janki Nath Kachroo, the former principal, who selflessly devoted 40 years of his service to this school,” Bhat said. “His methodic and innovative teaching in Science and English language gave National School students an apparent edge over the others.”

The School was known to give specific responsibilities to students in order to develop their specific capacities, Bhat continued. “In the long run, this would develop critical attitude, scientific temper and a sense of responsibility in students.”

Another school operating from the same premises

A Srinagar-based trader and an alumnus of National School, Peerzada Shabir recalls the 60s era of the School, when the free and frank teacher-student interactions would compel students to strive hard in studies and other spheres of the life.

“I remember how the academic atmosphere of the school was given a new and fresh direction in 1969, when the modernization for the School began,” Shabir said. “English medium sections were added and KG classes were started.” In 1972, an institutional plan was framed with the motive to achieve the decadal set goals.

But after the school building was gutted in a devastating fire in October 1982, it passed through trying times. The subsequent coming of turbulent nineties saw most of its workforce—the KPs—migrating from the Valley, leaving the responsibility of the School with a Managing Trust, which was dissolved in 2010 over its failure to fund and run the school properly. With the result, the government overtook it, only to reduce it to a sanctuary.

The power shift has already deepened the disaster. The poor-funding has eroded the School’s work culture and has made the administration to thrive only on student fees. The school offers very low wages to its staff—who’re sans salary from one last year, said Farooq Ahmad, one among the two non-teaching staff members of the School.

“The school cannot even afford a sweeper due to unavailability of funds.”

Perhaps the last nail in the coffin came in 2016 uprising when the school building was handed over to the extra-deployed CRPF in City. By the time they vacated it, they had left behind damaged school furniture and empty liquor bottles in classrooms. “It further created the negative image of the school and due to which scores of parents demanded to discharge their children from the school,” said the dejected school principal.

Today, National School’s condition has become a classic case of the abandoned legacy, which evokes lamentation than action. Perhaps the day isn’t far when the historic school might die its own death amid the growing official apathy towards it.