Since March 1997, the Mir family of Batkoot has been grappling with recurrent flashes of the butchery that saw their beloveds being put inside a pit to terrorize the already terrorized before forcing them to change the kill details.

The lazy Sunday at once turned frightening when a blast rocked Khanabal-Pahalgam road at dusk of March 2, 1997. The ear-shattering explosive rattled Batkoot, a pastoral village snuggled some 30km down in southern Kashmir’s Islamabad town, where villagers were chatting on shop-fronts and roadsides.

Running for cover, they squirmed through the throngs of public, entered their houses and latched their gates from inside. Many of them mistook the blast as an air crash. But the blast had happened for real, blowing up an Indian armed jeep coming from Pahalgam.

In that grim hour, a silence prevailed over Batkoot. A silence before the storm.

Some 400 meters from the blast site, a roadside single-storey house was about to change. It sheltered two brothers: 44-year-old forest department employee Ghulam Hassan Mir and 40-year-old Sona-Ullah Mir, a daily wager in Pahalgam Development Authority (PDA).

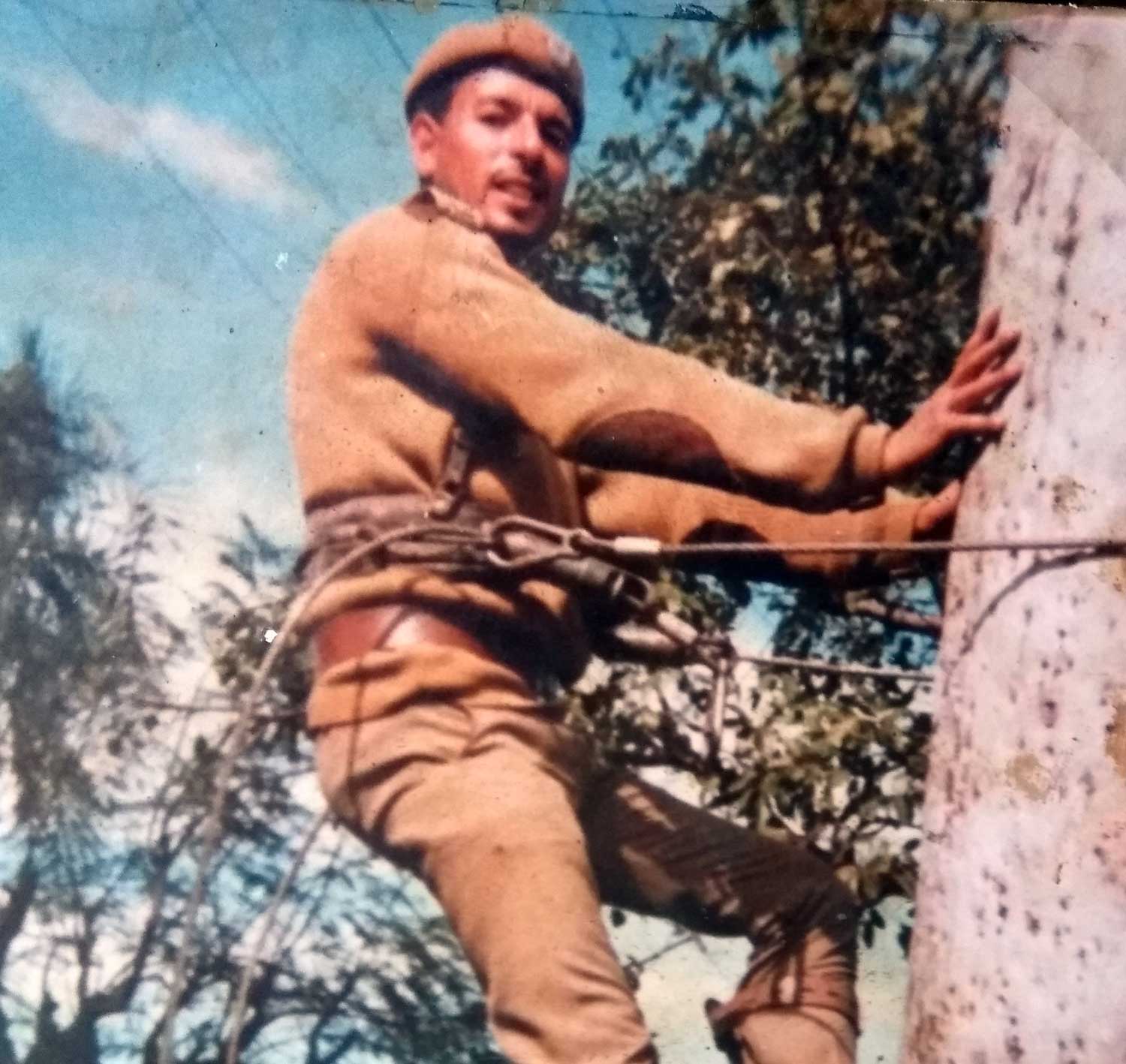

Picture of Ghulam Hassan Mir from the Mirs’ family album, while performing his duty in forest department.

Some half an hour later, the army cordoned off the whole area and stormed the Mir house. All the members were called out and put in a single row inside a cold lawn. Army personnel sans reasoning began beating the Mir brothers and Sona-Ullah’s elder son, Mohammad Iqbal Mir, who had recently finished his Class 10th annual examination and was waiting for his result. While the others were asked to stay inside, the terrified trio was dragged out of their house.

“Some five minutes later,” remembers Mudasir Mir, Hassan’s son, then studying in class 5th, “four intermittent gunshots rattled us. We rushed outside and saw my father’s body lying on the road in a pool of blood.”

When Hassan’s widow Naseema Banu, now 55, saw her husband’s body, she ran inside and took a glass of water. Squatted on her haunches, Naseema put the head of her bleeding husband in her lap and tried to give him water. Hassan died in Naseema’s lap.

Just 100 meters away from his brother’s body, Sona-Ullah was lying on the roadside, dead. His son Iqbal was shot at the blast site.

“All the three were shot at point-blank range in their chests, except my father who had one more bullet in his belly,” recalls Javaid Mir, Sona-Ullah’s youngest son.

Beating their chests, Naseema and Sona-Ullah’s widow Hajra Banu, now 50, cried in their shriek and wistful voices. After hearing the wails, hordes of neighboring women swarmed the road and gathered near Hassan’s body. After a couple of minutes, the army returned and chased away the women.

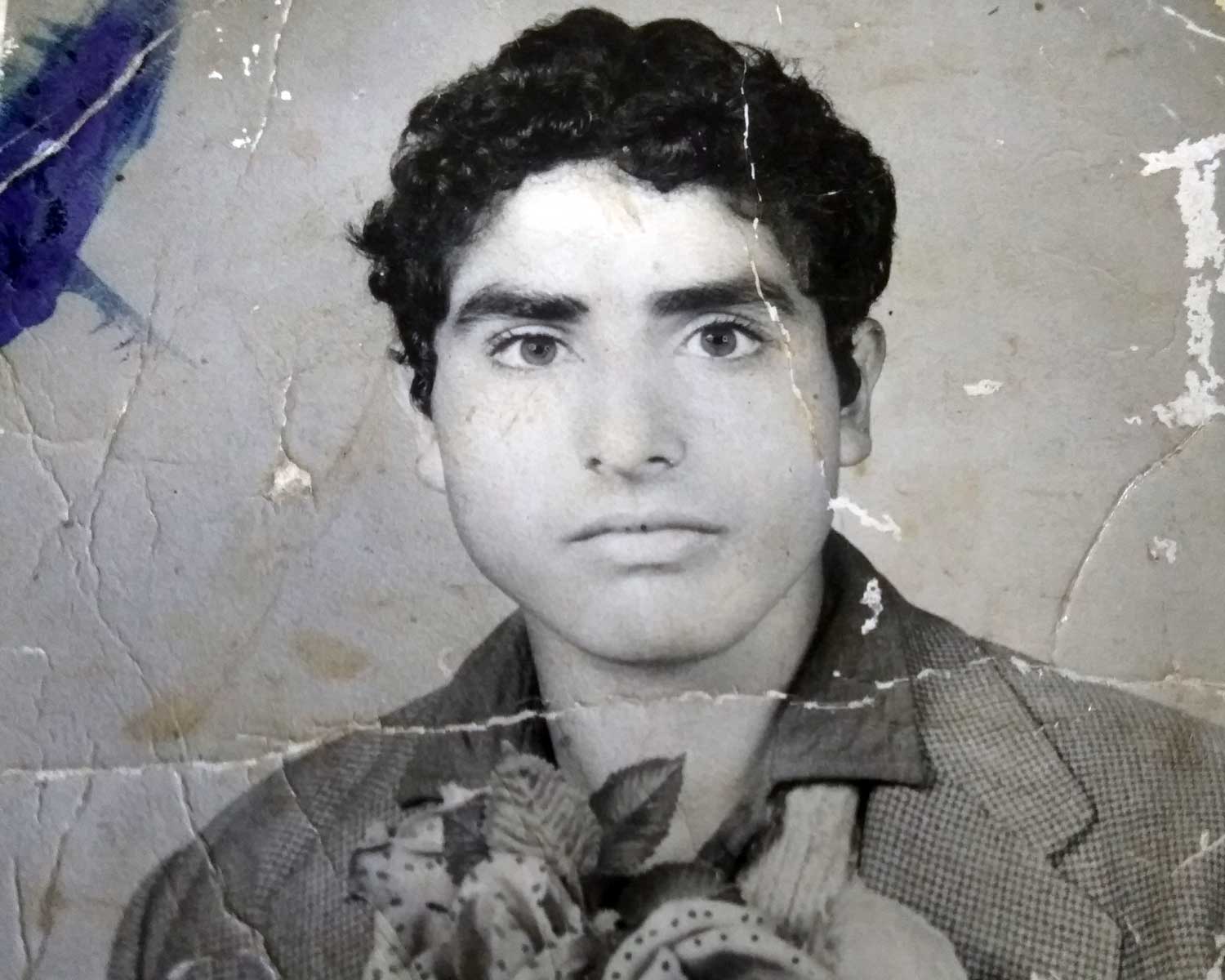

Picture of Sona-Ullah Mir from the Mirs’ family album.

“Murderous frenzy was clearly reflecting from the army’s actions,” recalls Mudasir. “They didn’t allow us to pick up the body of my dead father. Instead they dragged my father’s and uncle’s bodies and took them near the blast site, where the dead body of my cousin was already lying. They were thrown in the hole created by blast.”

Shortly after the army left, a villager announced the killings through a local mosque loudspeaker, triggering massive mourning in Batkoot.

“The dead bodies were kept in that room for whole night,” says Javaid, pointing towards a room.

Fearing return of the army, the villagers insisted the mourning Mirs to stay in their houses for the night, along with their dead. As the night fell over Batkoot, Army did return, cordoning off the village and dragging an octogenarian and revered villager, Khazir Mohammad out of his house.

“He was tortured and kept outside for the whole night,” remembers Mudasir, who along with his entire family stayed up in terror that night. “After 40 days of that incident, the torture took Khazir Soub’s life.”

By the next dawn, quick funeral was offered and the dead were buried in the nearby graveyard. Later that evening, as the grieving Mirs were sitting leaning against the walls, knees drawn to their chests, inside a room packed with lamenting visitors, the news broadcast from Radio Kashmir Srinagar at 7:30pm left them stunned.

“Everyone in the room turned numb,” says Mudasir, slapping the floor twice with his right hand, “when the newsreader said, ‘Aimed at army vehicle, three civilian were killed in a blast that took place in Batkoot area of Pahalgam.’ He even read wrong name of my cousin.”

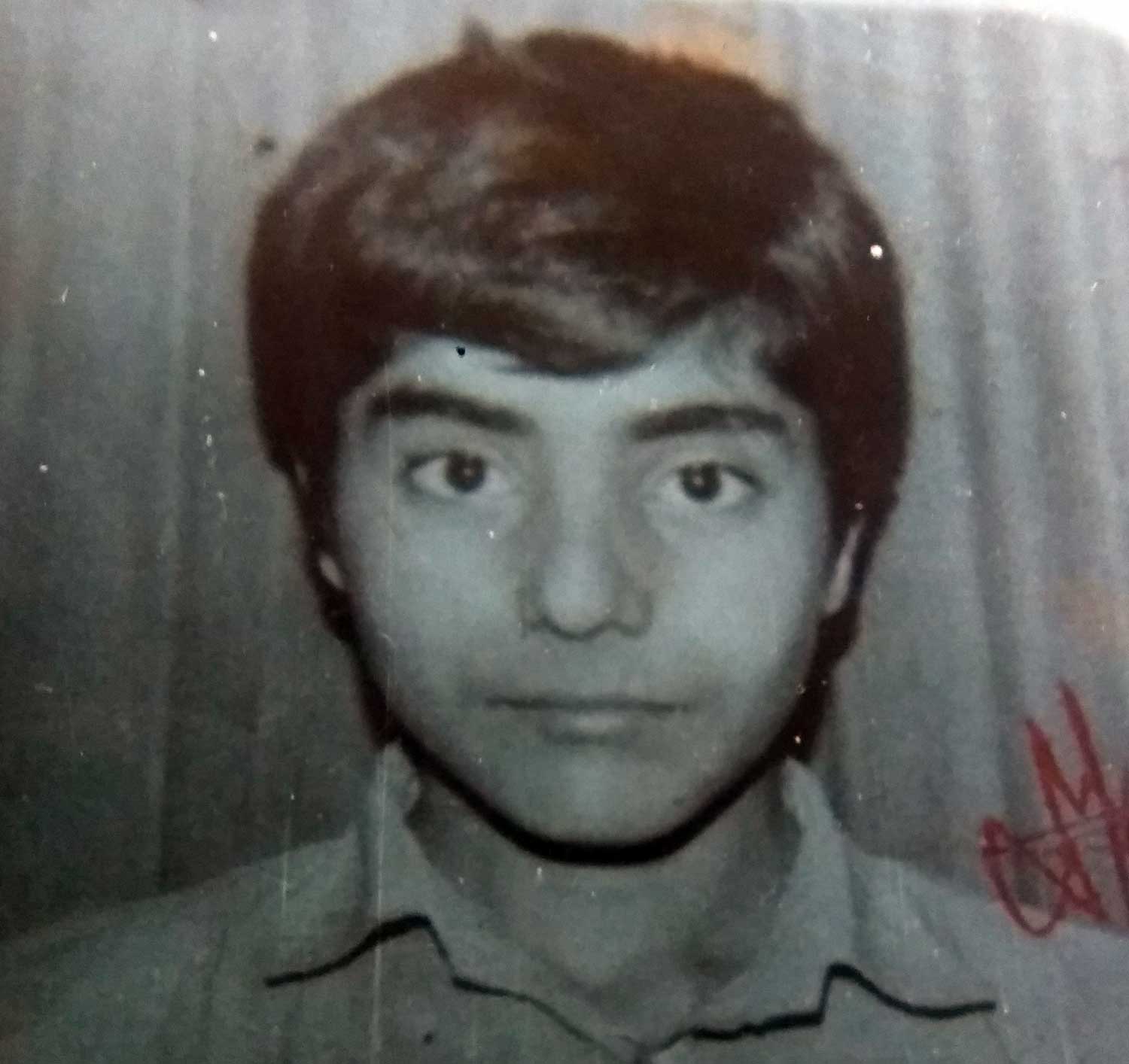

Picture of Iqbal Mir, Sona-Ullah Mir’s son, from the Mirs’ family album.

Radio Kashmir’s filtered news, then drawing flak from pestered public, only intensified the mourning.

“A few days later, when my elder brother gave his statement before the police, he was asked to change it,” Mudasir remembers. “Police told our elders that they wouldn’t be provided with non-involvement certificate, employment under SRO-43 and ex-gratia, if they wouldn’t change it.”

For the family whose breadwinners were gunned down in a matter of minutes in military drills that were the norm those days, the directive was read as more of a concealed threat.

The Mirs changed their statement before the police, stating that their members were killed in a blast. “When your eldest surviving male member happened to be a 16-year-old boy, then what else would you do?” asks Mudasir.

“He was not mature enough to take his decisions. Besides, Kashmir was going through a terrible time then. We were scared.”

After the police records show the cause of the the deaths as a blast and not bullets, the government gave Rs Two lakh to Sona-Ullah’s family (for two killings) and Rs One lakh to Hassan’s family, and a job to the each family in 1998 as compensation.

Hassan’s elder son and Sona-Ullah’s wife were appointed as replacement of their deceased family members in the Forest department and PDA respectively.

Decades later, the family is still confused whether they were given jobs under SRO-43 or in replacement of their slain breadwinners who were in same post before their killing. They even talk how they had to pay Rs 30,000 as bribe to government officials to clear their compensation of Rs 3 lakh.

The systemic silence followed by the institutional plague only worsened the woes for the Mir family, where the two surviving widows were fighting for their sons’ survival. They brought up their sons and gave them good education.

Besides his widow, Hassan had left behind three sons: Shabir Mir, Imtiyaz Mir and Mudasir Mir. Similarly, Sona-ullah’s widow had to take care of their three sons: Aijaz Mir, Gulzar Mir and Javaid Mir.

Had not it been a Sunday, says Mudasir, sitting with his cousin Javaid inside a room, his father and uncle would have been alive. Both used to come home late from work every day. “Magar khudayas kun shukur, muen boed boi ous’ni yeti tam’doh natte marhan tamis ti (But thanks to Almighty! My elder brother was not present at home that day. Otherwise, they would have been killed him, too),” says Mudasir, while talking about his elder brother, Shabir Mir, then 16.

But becoming fatherless in the times of great peril had its own costs for them. Fearing a repeat of the bloody Sunday, the Mirs installed grills on their open windows.

Two decades later, the iron grills continue to give a prison-like look to their home, making one believe that the blast from the past—on which a deafening silence still prevails—continues to horrify the Mirs of Batkoot.

The road where three members of the Mir family were shot.