A series of stories detailing the grisly events of 1947 Partition recently made rounds across India and Pakistan. In Kashmir, such stories brought home the historic horrors including the military blockade of the trade routes in Kashmir and the subsequent fall of Yarkand Sarai.

Walking through the historically, culturally and architecturally rich, and densely populated Shehr-e-Khas—Downtown—area of Srinagar city makes one to see some not-so-Kashmiri faces around.

Their facial features are an amalgam of Kashmiri and Ladakh populace. The way they act, look and talk is different. This polyglot tribe resides in Safakadal’s Yarkand Sarai, where Abdul Rashid Khan Rahgeer (Ladakhi) is a living witness, and raconteur of the tales that saw this significant signpost of Kashmir’s history dying the Partition-induced death.

Seated in Safakadal’s hustle-bustle ambiance, on the banks of Jhelum, the Sarai—somewhat different from the typical Kashmiris shelters—is separated from rest of the place with a green painted gate.

Beyond it, a different world exists. It’s a mini-neighbourhood wrapped with big banners with ‘Ya Hussain’ emblazoned on them. Sitting in this silent setting, a bunch of women are weaving something together, speaking a different language near their flats made of bricks, mud and wood.

FPK Photo/Hayat Manan

The spoken language and the ambiance make it some kind of ‘non-Kashmiri’ space. Without talking much, the women give the reference of one Ladakhi living in the community. “He knows this place very well,” they say, smiling. “He likes to talk about it and its history.”

Ladakhi’s address is a white painted door, where he appears following the knocks. A greeting smile on his fair face makes wrinkles around his eyes. The 64-year-old tall Ladakhi wearing a grey pheran gladly opens his door, following the mention of Yarkand Sarai.

A small room inside is full of crockery popularly sold in Ladakh. His wife brings some freshly cut red, juicy and tasty Ladakhi apples whose appetising smell wants one to grab a piece.

He sits near the rarely seen ‘Atish Daan’ room, smelling of mud, Devdar wood, stones and bricks.

“What’s the history of this place?” so you ask and leave everything him to say.

Abdul Rashid Khan Rahgeer (Ladakhi). (FPK Photo/Hayat Manan)

Ladakhi starts with the details of what Yarkand Sarai was, who would live there, who lives there now and how they got here.

The short story writer Ladakhi shares his story exactly like a storyteller, saying that a long ago, before the Partition of Indian Sub-Continent, the then princely state of Jammu and Kashmir would be lost in merriment. People would live simple lives and have connections with their neighbours and the neighbouring countries. Yarkand was one such country.

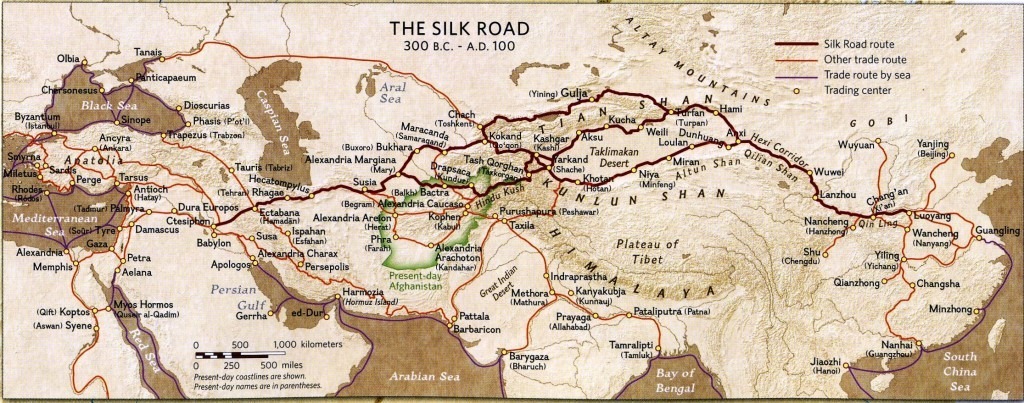

Located in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China, on the southern rim of the Taklamakan desert in the Tarim Basin, the place was the seat of an ancient Buddhist Kingdom on the southern branch of the Silk Road which was an ancient network of trade routes that were, from centuries, central to the cultural interaction connecting the East and the West.

Islam entered in Kashmir through Central Asia. That was the time, historians say, when Yarkandis started coming to Kashmir. Gradually, the Valley started getting influenced by the Central Asian culture. As the influence increased, traders started pouring in into the state.

They would travel in caravans. It would take them about a month to come to Kashmir—on tongas, horses or donkeys—crossing the mountains.

For the ease of trade, the then ruler of Kashmir Maharaja Pratap Singh got the Sarai constructed in Safakadal, so that traders and tourists could have a place to stay in Kashmir.

“These shops, the bank and the bridges you see now,” Ladakhi says, “they weren’t there earlier. The road was up high with a gate on it and policemen would be designated there. This area was a trade centre.”

ALSO READ: Kashmir, Chenab and the opening up of Kashmir to the world

Traders from all the areas including Rawalpindi, Yarkand, China, Dras, Kargil and Leh would come to Kashmir via the Silk route and stay in this Yarkand Sarai, he says.

The Kashmiri traders from Sheher-e-Khas would trade Pashmina Shawls, Carpets, Wool, Chinese crockery, Shahtoosa, Kashmiri Namda (carpet), stones, jewellery, dry fruits and all sorts of things with the foreign traders.

A middleman would come running to the Kashmiri traders, informing them about the arrival of the Kafila of foreign traders.

“They would come and hire a room on rent here,” Ladakhi fondly recalls the bygone foreign footfall making Srinagar a cosmopolitan City.

“They would pay Rs 2 per room, which was a big deal back then.” The travel-weary traders would sit together and decide whether they would take cash home or buy something with it from Kashmir only to sell it back home.

Gradually, the connections between Kashmiris and foreigners became stronger. Travelers and traders from China, Yarkand, Dras, Leh and Kargil started living in Kashmir. Some of them had chosen bakery as their profession and some had married their children here.

“Over the period of time, some Chinese, Turks, Yarkandis went back, some died here,” Ladakhi says. “Subsequently many went to Saudi, some to Turkey and others to America but their families or some among them continue to stay in Kashmir. One Yarkandi lives in Lal Bazaar today and the other two have probably shifted to Bemina.”

For the living, many Yarkandis would make and sell Naan-Kebab made of flour and sugar besides sausages on street cart. But their best delicacy would be Lagman.

“The Maggie noodles you see today are nothing in front of that Lagman,” Ladakhi says. “Yarkandis would make it with their hands. Its ingredients would be flour and eggs. They would beat them together and make noodles. Separately, they would prepare a dish of Cauliflower and mutton pieces. It was known as Kacha Pacca. Then they would pour a little Kacha Pacca on the noodles and eat them with hands/ fork.”

For 600 years, he says, this is how things were happening in Kashmir. Sufis, poets, artists and bureaucrats would come here. And then, the partition of Sub-continent took place. A part of Kashmir went into the hands of India, which banned the trade through Silk Route.

The Jhelum Valley Road, Silk Route and Bandipore Road that would connect Kashmir Valley with countries including Pakistan, China and Gilgit-Baltistan became militarised. After the ban on civilian movement on these routes, the Yarkand Sarai became the history’s passé signpost.

Before the partition, Ladakhi’s grandfather, Abdul Sataar had come to Kashmir along with his wife and two sons from Dras, Shimsha. With the subsequent bifurcation of Kashmir, his native village became the part of the Ceasefire Line, which later became Line of Control. In that hinterland, the usual rustic life was pushed beyond the boundaries.

In a post-haste, his grandfather went to Dras and could never come back. “My grandmother was devastated,” Ladakhi says, “but what could she do? There were no phones or even letters. They were illiterate. Moreover, they didn’t know where and how to post the letter.”

Eventually, his grandmother died in longing for her ‘divided’ husband. Ladakhi’s father married in Kashmir and started to work in a factory dealing with animal skin. Out of that wedlock when Ladakhi was born, he passed through twists and turns. He eventually became the first matriculate in his family and was appointed as a teacher. Years later, he was awarded as the best teacher by Mufti Mohammad Sayeed in 2007.

While growing up as a different Kashmiri craving for his roots, he never knew that he would have a brush with Kashmir’s armed uprising in late eighties.

The day when the first incident of firing took place in Kashmir in late eighties, he boarded an auto in panic while coming from the office. To his surprise, he saw the two Kashmiri men already sitting inside.

“I thought they belonged to JKLF,” he says. “They were saying: Freedom cannot be attained without sacrifice. It should not take too much to sacrifice. I stayed mum and got off as soon as I could.” Next time when he spotted a gunshot wounded man almost bleeding to death near Ali Masjid, Srinagar, he sensed how Kashmiris were up against the lingering political crisis created by the Partition.