New Delhi finally had its way when Srinagar was handed over to CRPF with Jagmohan’s appointment on Jan 19, 1990. The same day, a neighbourhood on the ghats of Jhelum became the spark point of Kashmir’s unflinching dissent.

When SSP Srinagar Allah Baksh suddenly turned up at Chota Bazaar on January 19, 1990, the first sign of radical shift in Kashmir’s militarised landscape appeared. New Delhi had finally cleared the decks for the return of the controversial administrator Jagmohan who only used his single name as JK’s new governor.

“Now behave,” Baksh was heard telling the Chota Bazaar locals. “It’s no longer in our hands.”

Before the vague statement could leave the locals confused, the helmeted and padded paramilitary force began arriving to replace the JK police on the streets of Chota Bazaar. The move was the indicator of a historic transition. The defiant Srinagar where freedom songs blaring from mosque speakers had made it an apparent liberated town was finally handed over to India’s largest central armed police force, CRPF.

“The moment CRPF was deployed,” says Ali Mohammad Kochak, a charcoal retailer in Chota Bazaar, who saw the history unfolding in the area that day, “the locals sensed the alarming situation as some of the hostile troopers began assaulting the locals around the bridge.”

With Jagmohan still cooling his heels in Jammu, the two local boys came out of their homes in a routine manner — perhaps oblivious of the harsher curfew imposed in the city. Near the bridge, Kochak saw the paramilitary men chasing them. They jumped over the fence of a nearby house.

“The two CRPF men also jumped inside the residence,” recalls Kochak, then watching the scene from his house window. “It panicked the women of that household, who shouted and alarmed the neighbourhood.”

As the screams echoed through, people came out with sticks, spades and whatever they could lay their hand on. “Even fishermen living in small houseboats came out with shovels to confront the CRPF,” the eyewitness of the episode says. After momentary street chaos, the CRPF forced the locals indoors again. But youth were still standing near the alleys, raising slogans.

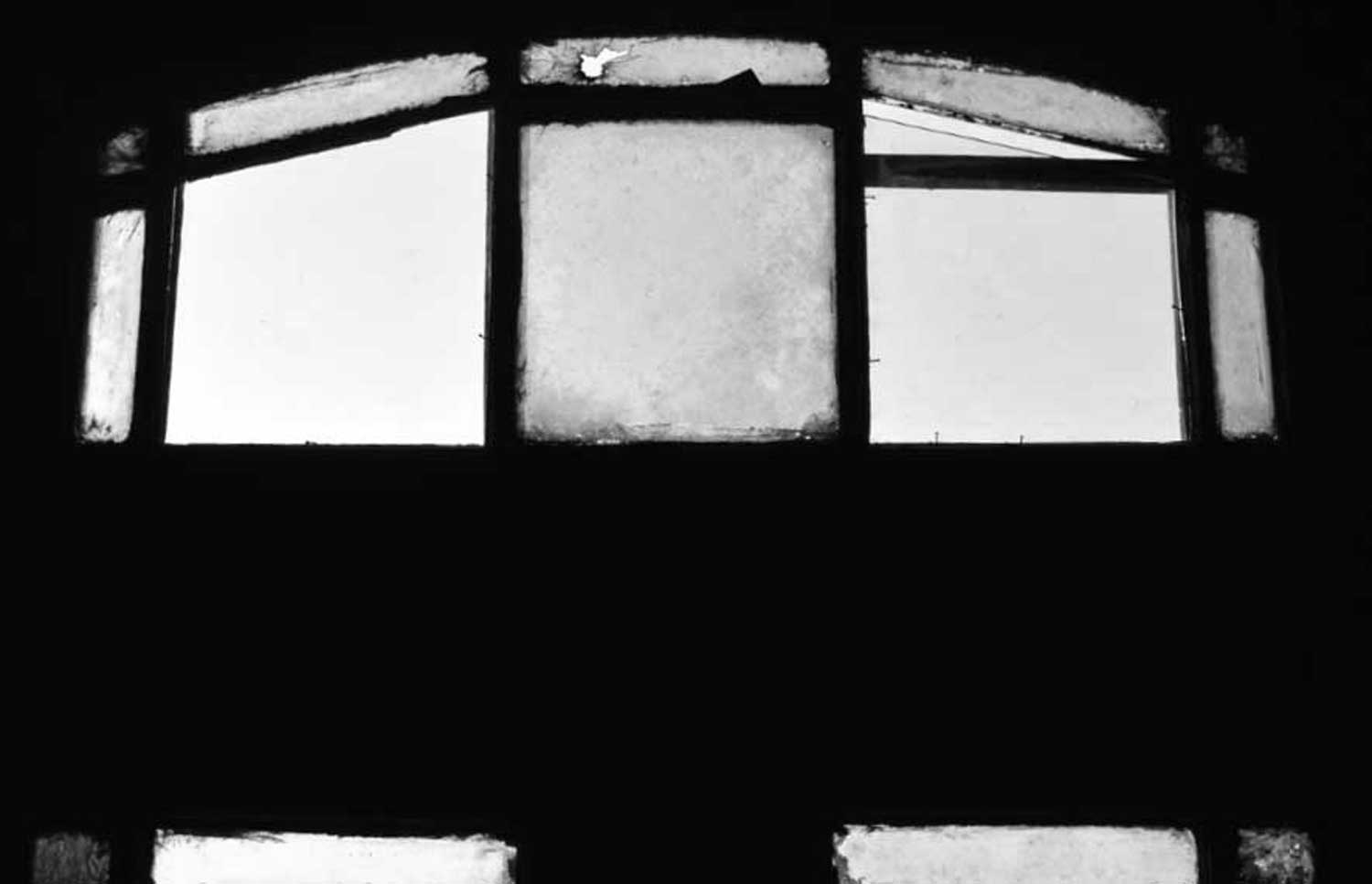

Mark left from the bullet, that went though an attic of one of the houses, during the first cordon operation at Chota Bazar. The attic has never been repaired. (FPK Photo/Hayat Manan)

Next day, on Jan 20, the entire township faced the first militancy-era cordon and search operation, now written as CASO in short spaced headlines. During that first ever CASO, women cops were called in to check the local women. Perhaps the episode was the first ominous sign of the times Kashmir was about to pass under Jagmohan’s four-month Raj Bhawan stint.

In that dawn raid, forces barged inside the houses, and dragged out the locals. One of them was Abdul Majeed Shah, a carpet dealer.

“Before taking me out on the first crackdown in Kashmir,” says Shah, now living in his new residence at Qamarwari, Srinagar, “the CRPF troopers enquired about my other family members.” His two minor sons were shaken up from the sleep and also taken out.

“I pleaded with them that let me wear clothes. They didn’t agree. I just put on my Pheran over my undergarments and came out with my sons—shivering in January’s numbing cold,” Shah says.

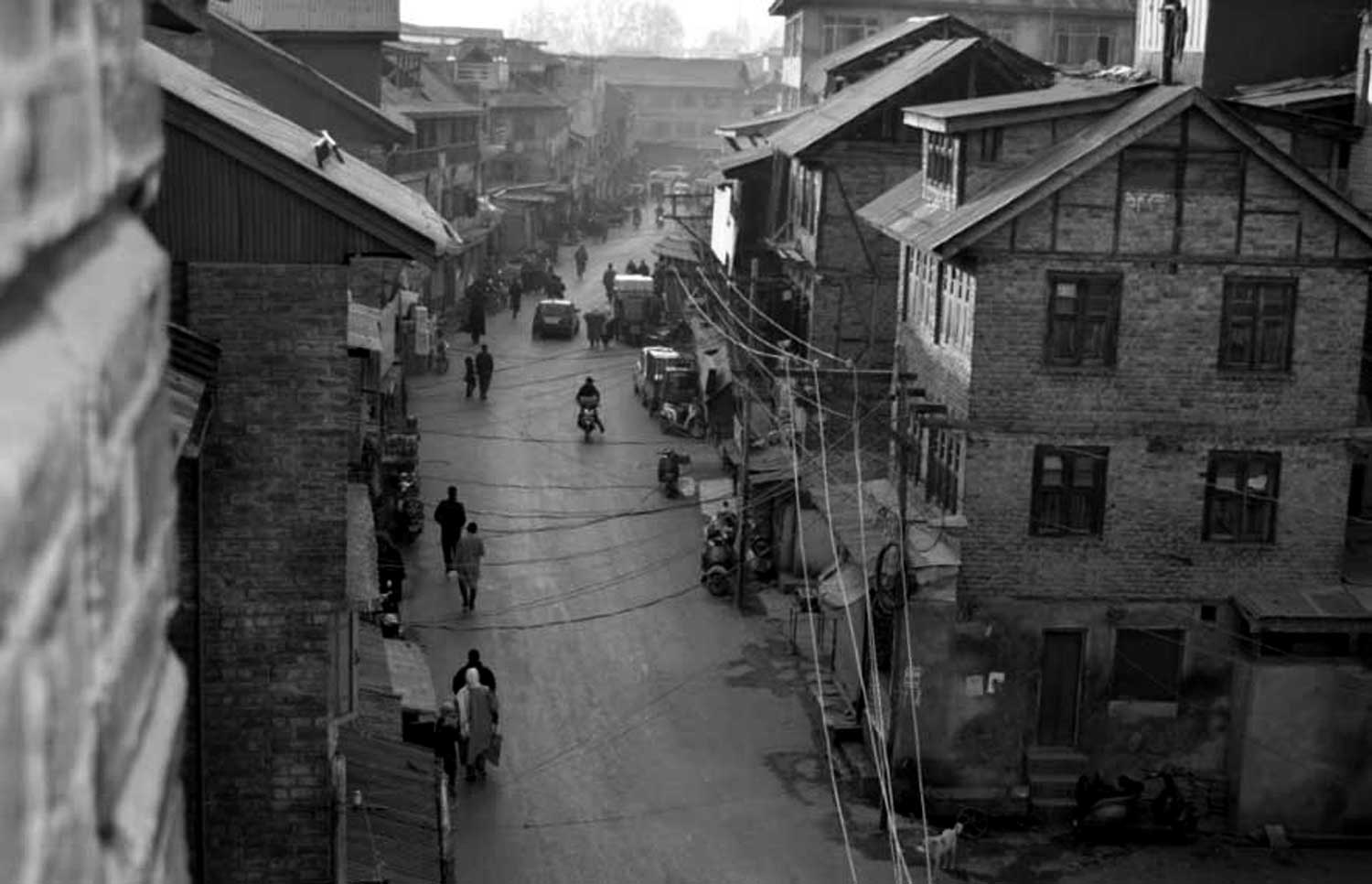

Chota Bazaar, present day. (FPK Photo/Hayat Manan)

On the main street, he saw a fleet of paramilitary trucks and buses ready to ferry locals to the nearby DC office, Srinagar.

“Lithnawik tatheth (We were beaten black and blue),” recalls Shah. “Even a mentally-unsound person had been detained.” From DC office, they were taken to Hari Niwas. On the way to that palace abandoned by the last Dogra Maharaja of J&K in the later part of 1947, Shah asked a trooper: What’s happening?

“Abdullah Raj khatam hogaya. Ab pata chalega. Governor Raj shuru hogaya (Abdullah rule is over and done. You’ll get to know now. It’s the Governor’s rule now),” Shah recounts that resounding remark on way to Hari Niwas, where some 450 men were thoroughly frisked and passed through an identification parade.

ALSO READ: Jagmohan: He came as a ‘nurse’, but…

“For the first time,” Shah says, “we were made to stand in a line and passed before a masked man for identification.” Later such masked men came to be known as CATs.

Once done with the parade, a high-ranking Sikh officer came and made the scantily-dressed locals to sit on a mat in a bitter cold. Then, the SSP Srinagar Allah Baksh arrived with an assurance. “Don’t worry,” Shah quotes him as having said. “Nothing is going to happen to you.”

For the whole day, Shah says, his townspeople were being summoned into the building and questioned. From windows, he could hear cries.

“There were government employees among us, too,” he says. “They thought they might be spared. Dey Choab (They were thrashed like anything).” Many people later recalled how they were grilled for living in the native place of JKLF top militants like Javaid Mir and Bitta Karate. Then Karate would trend as the notoriously-famous hit-man trailing the “sleuth Pandits”.

By the evening of January 20, 1990, when Jagmohan was done with his “intimidating” televised speech from Jammu, a curfew relaxation in Srinagar was thick with talk of molestation at Chota Bazaar and adjoining Guru Bazaar. With all the men detained at Hari Niwas, the next morning dailies wrote, many women were molested.

Later that day as guns fell silent after raging on human bodies at Gaw Kadal where fire was opened on the procession heading towards Chota Bazaar in solidarity from civil lines, Peer Mohammad Amin, the Chota Bazaar headman went to meet Jagmohan, who had landed in Srinagar soon after the massacre.

“In presence of chief secretary Hameed Banhali, I asked him: ‘What’s this? You said you’ve come as ‘Nurse Orderly’. What did you do in your first day as governor? Is this your idea of handling Kashmir?’ He told me to talk to Banhali in my own language. ‘But I can speak with you in your own language, too,’ I told him.” The face-off ended after the locals were released—except two, who were set free six months and a series of tortures later.

By the time the duo walked out, Kashmir had changed. Jagmohan was back to Delhi after presiding over multiple massacres. And Chota Bazaar had become the ‘urban legend’ in the seething Srinagar.

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.