As the Article 35-A row intensifies, an 82-year-old Kashmiri Pandit recently caught people’s eye after he spoke against its abrogation during a sit-in at Srinagar’s Pratap Park. But before becoming the fiery face of the campaign, Sampat Prakash’s tryst with the issue had begun in 1968 when he was arrested under a law passed by the Indian Parliament.

As the crusade in defence of Article 35-A is building up in Kashmir, an octogenarian man lately made his public appearance in Srinagar with a fiery speech against the judicial assault on the state’s unique identity. Some fifty years ago, the card-carrying Communist’s accidental petition had sealed the fate of the state subject law in the Indian apex court.

But at the behest of sponsored litigations now, Sampat Prakash Kundu has once again become the star campaigner of the law which gives Jammu and Kashmir state subjects exclusive rights over property, government jobs and scholarships in the state.

However, before playing his part in the judicial affair, Sampat got his grooming in the tumultuous period of Kashmir’s history.

As a CM Tyndale Biscoe School student, he saw his father Neel Kanth Kundu—the revered headmaster at the school—backing the Kashmiri Nationalist movement as a staunch supporter of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, whose slogan “Sher-e-Kashmir Ka Kya Irshad… Hindu Muslim Sikh Itehaad” had held the masses together.

Sampat remembers the day his father admitted him in the school. After an hour, he says, Sheikh Abdullah also came to admit his son, Farooq Abdullah. “Sheikh told my father: ‘You’re a reputed teacher who teaches in a reputed school which has produced so many jewels. Here is my son. Keep him in that company only’.” As roll number 29 and 30, Sampat and Farooq shared the same desk.

Back home, as Sampat was learning Kashmiri Nationalism from his father, Sheikh was drafting his Naya Kashmir Manifesto. Among the late Prime Minister’s advisors was Sampat’s father.

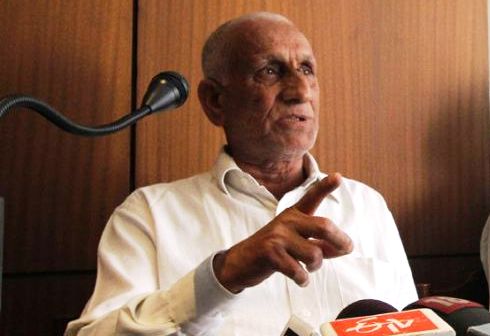

Sampat Prakash during a protest against the abrogation of the Article 35-A.

“My father used to tell me that Kashmiri Muslims are oppressed people,” he says, “as they are being subjected to forced labour.” Then his neighbour in Old City’s Rainawari, Ragunath Matoo, the then Wazir-e-Wazarat—akin to today’s deputy commissioner—would carry out the ‘governance’ which included forced labour.

“My father would speak against him, telling him ‘Zulmuk Mumbe Chu Yuhai’ (Matoo is the fountainhead of oppression). Both were well-known and respected men in their field of work. My father’s work was education, while Matoo’s was to carry out the orders of the Maharaja.”

As ‘recruiters’ for forced labour, Sampat says, Kashmiri Pandits were always Naukar-Peaish (servant mentality) and loyal to the rulers of the yore. Growing up with all these impressions and encounters made him a curious person. His father would advise him to study Sir Walter Roper Lawrence’s The Valley of Kashmir for understanding how the Revenue department—then ordering and sending Kashmiri Muslims on forced labour—was entirely a Pandit territory.

ALSO READ: Meet comrade Gulshan Majeed, the Naxalite movement’s bygone Kashmir campaigner

“There is a hole in my heart due to this,” Sampat recalls his father saying. “The worst part is that a Kashmiri is exploiting his own fellow Kashmiri. This has to end.” Soon as he was introduced to Sufism and Kalhana’s treatise by his father, Sampat started taking pride in his identity.

Then as Afridis arrived in Kashmir during the eventful fall of 1947, Sampat as a young boy first came out to protest along with his father on the call of ‘Sher-e-Kashmir’, where Hamlawar Khabardaar, Hum Kashmiri Hain Tayaar (Beware invaders, we Kashmiris are ready) slogan resounded.

“The essence of that protest is still in my blood,” says Sampat.

Peace Brigade of the National Conference.

In 1953, when Sheikh was arrested, Sampat got enrolled in Srinagar’s SP College, where he organized student protests and called for a formation of a student union body. “As around 1900 people lost their lives in pre-Sheikh protests, I organized a student protest and gave a speech,” Sampat recalls. Soon as the Kashmir Students Union was founded, Sampat became its president.

During the same time, he was introduced to Marxism by Professor Hridaynath Durrani, who was his next-door neighbour in Rainawari.

“It was he who gave me classic communist literature such as Liu Shaoqi’s How to become good Communist and Lenin’s One Step Forward, Two Steps Back,” he says. “Durrani made me understand the basics of communism and eventually I became a communist.”

In 1958, when Sheikh was released, Sampat was already a student leader. That year, as he went to appear for his final year exam, he was picked by Inspector Qadir Ganderbali’s men from his exam centre in Islamia College and was lodged in KothiBagh for around 10 days. “I missed my papers and lost one year of education,” he says.

Once out, he would frequently enter into skirmishes with Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad’s civilian militia called ‘Gogas’. It was during those politically uncertain times, that his erudite father sent him to Jammu to study Law.

Six months into his studies, Communist Party of India organized a mega rally in Jammu. As all the bigwigs of the Communist Party were there, the young comrade couldn’t give it a miss.

“There the idea struck me that freedom is our birthright, even the Heavens cannot snatch it,” he says.

The next day he went to search for the CPI office in Jammu for availing the literature. “I was greeted by big comrades like Ram Saraf, Krishan Dev Sethi, Girdharari Lal Dogra,” he says. “As I introduced myself, they surprised me by saying that they already knew me as my name would often come up in their party meetings.”

That was the end of his Law studies.

He decided to become a full timer and planned to do tuitions so that his expenses were met with. Then one day, Ram Prasad Saraf told him that the party wanted him to play a bigger role.

He was told that there existed no Employees Federation for 3.5 lakh government employees in the state, when there already existed one in India since 1939. Why don’t you join govt service and lay foundations of an employee’s union, Sampat recalls Saraf telling him.

He didn’t have any second thoughts.

Soon Saraf through Mir Qasim, the then revenue minister, adjusted Sampat as an inspector in Custodian Department and was allotted a house in the Residency Road.

But rather than concentrating on the job, he worked for his party and his mission of bringing up an employee’s association.

After a couple of meetings with employees of various districts, All J&K Low Paid Government Employees Federation came into being with Sampat as its founding president.

“We drafted the Constitution and went to GM Sadiq and requested him to register it,” Sampat says. The Association was recognized in 1964.

With that, Sampat started raising the grievances of the state employees and took the Federation to all the districts. “We then made separate unions for teachers, for Class IV employees, Rural Development, Power Development, etc. They all were affiliated to the Federation.”

Around 37 unions were created for as many departments.

“We made it sure that like-minded people—liberal, progressive, educated, fighters and anti-Sangh— joined the Federation,” he says.

After coming to know about his suspended law studies, Sampat’s father was left disappointed. “But he was happy too, to see his son as a part of a movement.”

In Kashmir Valley, Sampat’s Red Movement had started creating a wave. As he called for a two-day strike, demanding Central Daily Allowance, appointment of the Pay Commission and other grievances of the working class, he faced suspension and jail. “But that suited me,” he says. “As I started getting half salary every month, I decided to go all guns blazing.”

Then in 1968, Sampat gave the call ‘Pen Down, Chalk Down, Tool Down and Wheel Down’ protest.

Pen Down was for the employees, Chalk Down for teachers, Tool Down for transporters and Wheel Down was for the State Motor Garage.

That was an indefinite strike and accepting the demands including pay hike was a big burden for chief minister GM Sadiq.

At that time, the Naxalite Movement had started in India. “We became their supporters,” he says. “Indira Gandhi was the premier. She couldn’t have tolerated that government employees would support an armed struggle. So, she called up Sadiq and told him that Naxalism should not take roots in the valley.”

New Delhi’s fears were genuine. Already the mood in the valley was militant as the employees in Kashmir were supporters of Plebiscite and Right to Self Determination, as was promised to them.

During the same time, as Sampat declared that Kashmir is occupied, he had to go underground. He received support of All India State Government Employees Federation.

“Now I had around 60 Lakh employees with me across the country,” he says. “I could take on the Government head on. They gathered support and many MLAs including George Fernandes came to the New Secretariat in Jammu and protested and demanded the release of all those arrested during the Pen Down strike.”

He was caught in a very dramatic manner.

One day as an underground comrade, he was returning home from Kolkata after attending a meeting. The secret police was already watching his house and had ‘be-friended’ his toddler son, named Lenin, after the famous Marxist revolutionary.

The day he came to see his family, his son got excited and went out and told them: ‘My Dad is home.’ That’s how Sampat was arrested on 18 March, 1968.

But little did he know that this arrest would make him the first state subject of Jammu and Kashmir to stand up for the Article 35-A.

For a week, he was at the interrogation centre in Jammu. “It was intense but there was no physical torture,” he says. “They wanted to know about my other comrades. I didn’t tell them anything.”

Sampat was subsequently shifted to the Central Jail Jammu and kept in solitary confinement.

“That made me furious. I was not a criminal. And nothing adverse had taken place throughout our agitation. I decided to teach the superintendent of the jail, Jaswant Singh, a lesson. He was notorious for ill-treatment towards prisoners,” Sampat recalls.

The next day when Singh opened the door of solitary confinement, he was greeted with a resounding slap from Sampat.

“He conceded to my demands and let me stay with other prisoners,” he says. It was there he met members of the Plebiscite Front, including their general secretary, Ghulam Mohammad Badarwahi.

He spent four months in Jammu jail and it was during that time he learnt a lot more about Kashmir history.

In the course of those four months, his wife, Dura, used to visit him regularly with their two sons. One day, he was told that his wife had come to see him. “I went into the superintendent’s room, where I used to meet her. She was not there. Instead I was told that there is an order to shift me to Reasi Jail. Along with Baderwahi, I was packed in a police car and shifted.”

After facing “horrible” prison treatment there, he wanted revenge.

“I as a political prisoner had been given a blanket and two convicts to help me,” he says. “One day, I asked one of the convicts to come to the cell with a pair of scissors. I cut up the blanket and used it as a rope to help the convict, who was serving a life sentence, to run away! The superintendent was suspended after the event,” Sampat says while bursting into laughter.

However, the underpaid jailer, the likes of whom were represented by Sampat, respected him. Out of that respect, he gave him a copy of Preventive Detention Law, under which Sampat was arrested.

“There I saw it,” he says. “The Law was against the Constitution of Jammu and Kashmir and I decided to challenge it. I went to Baderwahi and asked him that would he like to do the same. He declined by saying that he doesn’t believe in the Indian Law and courts.”

But Sampat gave it a thought.

“I took my judicial privileges,” he continues. “This act would apply on an Indian citizen. How can it be applied on me if the act has not been passed by the State’s Legislative Assembly?”

So, with the help of the jailer, Sampat wrote to the Chief Justice of India about his circumstances.

He kept the letter (writ petition) ready till his wife came for the monthly visit.

“I told her to post it in Pathankot as any letter posted within Kashmir would have been intercepted by the agencies and secret police,” Sampat says.

The Supreme Court of India received the letter in the first week of May in 1968. Soon as the court ordered that Sampat should be produced before it, he was taken to Delhi and lodged in Tihar Jail.

“The Tihar administration was briefed that I was a dangerous Naxal, so they locked me up with a man called Natwarlal,” Sampat says.

His jail-mate was the same conman who infamously sold the Taj Mahal thrice to gullible foreigners.

In the Supreme Court, meanwhile, the debate started regarding Article 35-A which prevented the application of Preventive Detention Act on a resident of JK.

“It was a five member Constitutional Bench and they upheld it because of Article 35-A. They gave a judgement that the detainee is not a convict; power to detain is not a power to punish according to subject. There was a debate for 11 days regarding my matter in the Supreme Court,” he recalls what became the Sampat Prakash v/s State of Jammu & Kashmir & Anr case of 10 October, 1968.

It was then, Sampat says, Article 35-A came into the spotlight.

ALSO READ: As D-Day over 35-A approaches, floodgates might open in ‘indifferent’ Jammu, Ladakh

However, the lawyers told the Chief Justice that the matter should be referred to a larger bench for further discussion.

“At that time the apex court had only 11 judges. They said that someone might again challenge the validity of the Presidential order,” Sampat says.

After a month, the hearing began.

“For a couple of days the full bench deliberated and came out with a judgement that Article 35-A is right. The act cannot be applicable on the detainee till the Legislative Assembly of the state will not pass it with its own provisions.”

It became banner news in All Employee’s Federations journals and Sampat became the celebrated comrade.

Almost 50 years later, as the state subject law came back into the spot light, Sampat decided to defend it.

“I met AG Noorani, Ram Jethmalani, Nandita Haksar, Prashant Bhushan and Sham Lal Papoo in 2015 regarding it,” he says. “All of them said since the judgement was given on it by a full bench, therefore Supreme Court has no power to entertain any plea on it.”

But after a bunch of petitions were filed against Article 35-A, Sampat says, the roots for the judicial assault were sowed during 90s.

“After Kashmiri Pandits fled away due to the fear psychosis created by Jagmohan, Indian Parliament, Government, Army, their intellectuals, their think tanks, decided to do it,” Sampat says. “Jagmohan was just an instrument to destroy our 5,000-year-old history at the behest of RSS backed outfits like Panun Kashmir.”

But now, he says, the biggest shield against the judicial onslaught is not in the court but outside it.

ALSO READ: Hearing on Article 35A: Is the State Govt’s defence ‘extremely weak’?

“It is inter-community dialogue which is not there as of now,” he says. “All the renowned doctors, engineers, bureaucrats, both Muslims and Pandits should have a sit-in for two hours at the Sher-e-Kashmir Park. KAS officers in the Secretariat should come out, even for 15 minutes and protest. Staff of the medical colleges should join in. But, it should be a Pandit-Muslim protest. Such camaraderie will derail the sponsored campaign unleashed to destroy our identity.”

Kashmiris are winning on the both fronts, he reckons.

“If they dismiss the petitions, it will be the moral defeat to Hindutva,” he says. “But if they manage to abrogate it, Phir Toofan Ayega… Jaise French Revolution…”

Like this story? Producing quality journalism costs. Make a Donation & help keep our work going.